skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Portrait Painter's Tips, Tricks, Musings, Methods, Materials, Demos & Paintings

Search This Blog

PAINTING CHILDREN, OCT. 2-6, 2017

MY PHOTOS: The Pulido Studio intensive workshop on Classical Realism

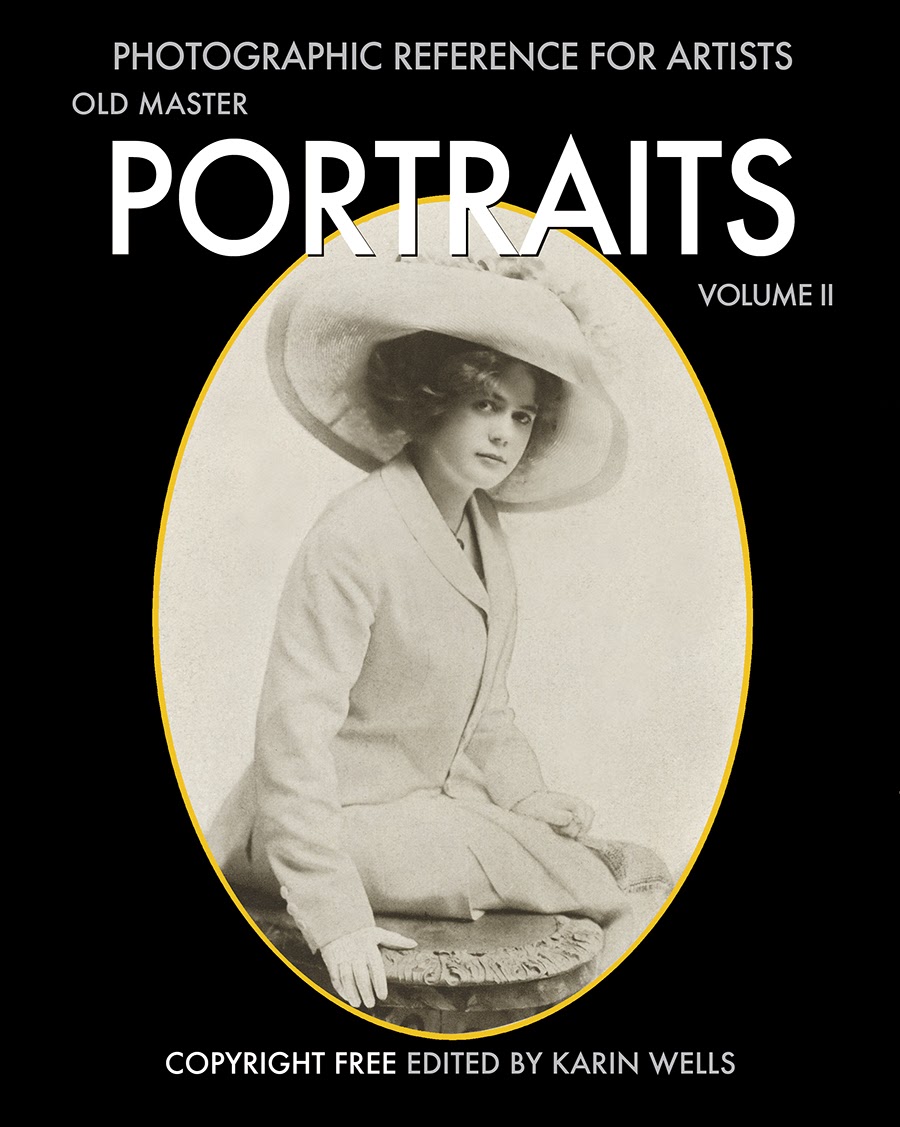

PHOTOGRAPHIC REFERENCE FOR ARTISTS ~ COPYRIGHT FREE ~ DOWNLOAD ON IBOOKS

Subject Index

- "Portraits of Americans Who Tell The Truth" (1)

- 10000 Hours (1)

- 9/11 Truth (2)

- A welcome from Karin Wells (3)

- A. Boogert (1)

- Abbott Handerson Thayer (1)

- Absinthe and the bohemian artists (1)

- Acetate (1)

- Acrylic Paint Palette (1)

- Acrylic paints Chalk for Drawing Lines (1)

- Allergies (1)

- Animal (12)

- Art Cards for Sale (18)

- Art Scams (1)

- Art Supplies I Love to Use (13)

- Art Teachers (1)

- Articles of Interest (2)

- Bazerman Effect (1)

- Bill Clinton (1)

- Bill Gekas (1)

- Blocking Edges (1)

- Blush (1)

- Books (5)

- Bubble Wrap Menace (1)

- Budda Board (1)

- Camouflage (1)

- Canvas (1)

- Caravaggio (1)

- Chuck Close Advice (1)

- Classroom History (24)

- Clinton (1)

- Clothing (1)

- Color (10)

- Color Banding (1)

- Color Mixing Book (1)

- Conservation (1)

- Contact Karin Wells (2)

- Copyright Free Resources (3)

- Copyrights (1)

- Counterintuitive Painting (1)

- Creativity and insanity (2)

- Critique (3)

- Dafen Village in China (1)

- Dear Readers 2009 (1)

- Dear Readers 2010 (1)

- Deb's Classroom (1)

- Demo (2)

- Disney Artists (1)

- Djordje Prudnikoff Fraud Alert (1)

- Don't paint an open mouth (1)

- Doris "Granny D" Haddock (1)

- Drawing (10)

- Dryers (1)

- Earth Palette (2)

- eBook (1)

- Edges (2)

- Egg Tempera (1)

- Encaustic Painting (17)

- Ethics (1)

- Figure (1)

- For Sale (6)

- Frame Nameplate (1)

- Frame Source (1)

- Frames JFM (1)

- Fraud Alert Djordje Prudnikoff (1)

- Free Advice Is Worth What You Pay For It (3)

- Fun (42)

- Gadgets (2)

- Genesis (1)

- Giclées (25)

- Giving It Away (2)

- Gladwell (1)

- Granny D (2)

- Grapes (1)

- Graphite (1)

- Grounds (1)

- Guidelines to consider for a successful portrait (5)

- Halftone (1)

- Hard and Soft Edges (1)

- Henri (1)

- Holiday (18)

- Holidays (1)

- How I painted Gwyneth (5)

- How I painted Joanna (5)

- How I use use black to make blue (1)

- How to build the dead layer (2)

- How to Draw an Ellipse by Eye (1)

- How to finish a painting (1)

- How to get a likeness (2)

- How to layer warm and cool paint (4)

- How to make a good composition (3)

- How to make a good reference photo (1)

- How to make a grisaille (2)

- How to make a reference photo (9)

- How to make an imprimatura (1)

- How to make an oil sketch (2)

- How to make an underpainting (2)

- How to make your work archival (2)

- How to manage edges (4)

- How to manipulate a reference photo (5)

- How to mess with reality - and why (4)

- How to paint an animal into a portrait (1)

- How to paint drips drops and details (3)

- How to paint in layers (1)

- How to paint realism (1)

- How to paint reflected light (1)

- How to photograph your artwork (1)

- How to roll a painting (1)

- How to transfer a drawing (2)

- How to underpaint for encaustic (2)

- How to use a "Budda Board" (1)

- How to use a golden rectangle and the golden section (2)

- How to Use Acetate Instead of Tracng Paper (1)

- How to use costumes and props (1)

- How to use lighting (2)

- How to use Old Master color banding (3)

- How to use Photoshop (4)

- How to use sfumato (1)

- I Love a Pun (8)

- iBooks (1)

- iBooks for Artists (3)

- iBooks Series (1)

- Ice Storm of '08 (3)

- Imprimatura (6)

- Imprimatura Basics (1)

- In Memoriam (1)

- Inspiration (3)

- Interview (1)

- iPad (3)

- iPad best tool (1)

- JFM Frames (2)

- Jobs (1)

- John Garcia (2)

- John Philip Simpson (1)

- Just for Fun (1)

- Kiva Microloans to Change a Life (1)

- Koo Schadler (1)

- Landscape (13)

- Leonardo's likeness (1)

- Luis Meléndez (1)

- Lyme disease (1)

- Mac (1)

- Malcolm Gladwell (1)

- Massing Objects (1)

- Mediums (1)

- Michelle Obama (1)

- Mitchell Bailey (1)

- Motivation (1)

- Movie (1)

- Museums (3)

- Music (1)

- Musings (5)

- My Palette (1)

- Neale Donald Walsch (1)

- Nelson Shanks (1)

- New Work (1)

- News (16)

- Notice (2)

- Numael and Shirley Pulido. Pulido. Workshops. Learn Classical Painting (1)

- Obituary (1)

- Obvious Advice (1)

- Off and on the walls (1)

- Oil Painting Factories (1)

- Oil Sketch (2)

- Old Book (1)

- Old Master Earth Palette (1)

- Old Master Portraits (1)

- Old Master Portraits Volume I (2)

- Old Master Secrets (4)

- Old Master Tips and Tricks (1)

- Old Masters (4)

- Original Paintings for Sale (31)

- Paint from life? No. (1)

- Paintable Clothing (1)

- Painting Annie (1)

- Painting Pearls (1)

- Palette (10)

- Pancake Method (1)

- Pearls (1)

- People (11)

- Perfection (1)

- Personal (2)

- Perspective (1)

- Photographic Reference (2)

- Photographic Reference for Artists (4)

- Photography (10)

- Politics and Religion (57)

- Portrait (20)

- Portrait Painter's Job (2)

- Portraits (1)

- Portraits - Historical (2)

- PSOA 2008 (7)

- Quiet Brush (1)

- Quote (2)

- Quotes (44)

- Recent awards (7)

- Reference Photography (1)

- Reference Photos (1)

- Robert Genn (1)

- Robert Shetterly (1)

- Roses (1)

- Roses iBooks (1)

- Screen Shots (1)

- Sfumato (1)

- Shadow Patterns (1)

- Shanks (1)

- Shows (3)

- Silhouettes (1)

- Single source of light (1)

- Sky and Clouds (1)

- Solving Light and Dark Problems (1)

- Song (1)

- Sotheby's (1)

- Spoof Ads (1)

- Staffage (1)

- Still Life (20)

- Studio Incamminati (1)

- Studio Safety (5)

- Studio Tour - Karin Wells (12)

- Studio Tour - Rembrandt (1)

- Studio Tour - Rembrandt part 2 (1)

- Studio Tour - The High School Art Teacher (1)

- Susan Boyle (1)

- Symmetry is for animals (1)

- Synesthesia (1)

- Talkin' technical (2)

- The Art Spirit Book (1)

- The universal color of light (1)

- Tips and Tricks (14)

- Transfer a Drawing (1)

- Truism (1)

- Truth of 9/11 (4)

- Ugly Art (1)

- Unprofessional (1)

- Useful Tools (1)

- Venetian Masters (1)

- Video Clip (32)

- Video Mimics Steps in Classical Painting (1)

- Vigee LeBrun (2)

- Volume I (1)

- Vote (1)

- Walt Disney (1)

- Warning (1)

- Why Beauty Matters (1)

- William Morris (1)

- Workshops (1)

- Your Name Tastes Like Purple to Me (1)

- Zinc White (1)

- My Painting Studio

- Peterborough, New Hampshire, United States

- Life obliges me to do something, so I paint classical realism ~ and share how it is done. I hope it helps you because the world always has room for more good art....and the artists who know how to produce it.